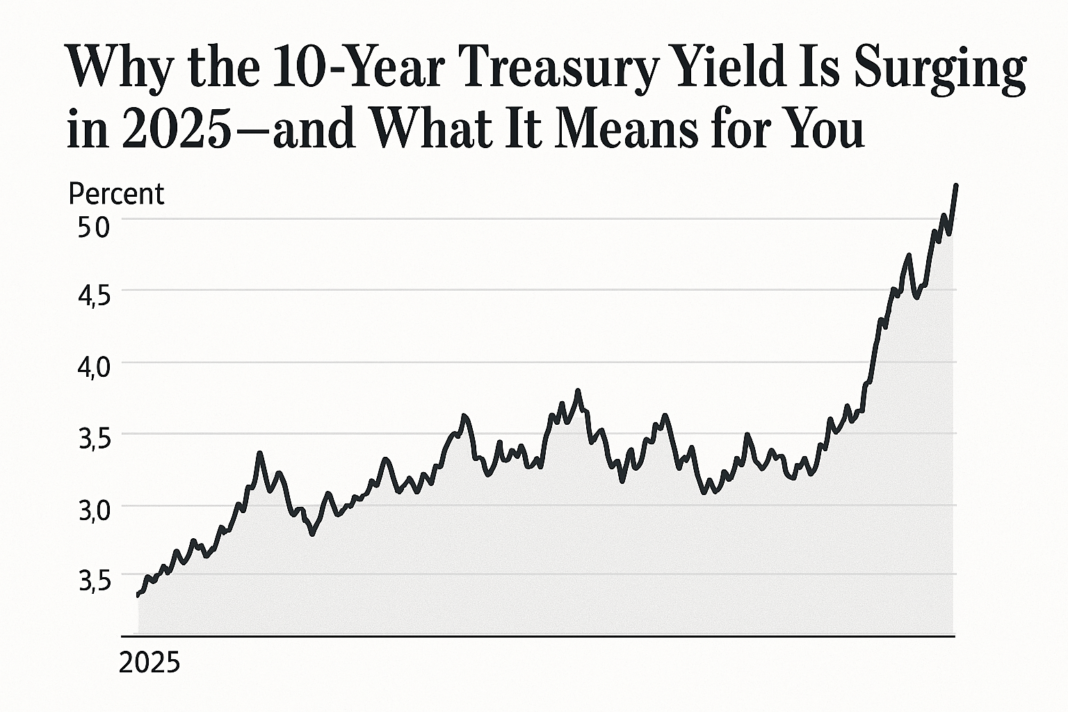

The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield—a bedrock benchmark for global finance—has surged to levels not seen since before the 2008 financial crisis.

Climbing above 4.85% in recent days, the yield’s ascent has unsettled financial markets, raised borrowing costs, and rekindled concerns over the trajectory of inflation and monetary policy.

For investors, homeowners, and policymakers alike, the yield on the 10-year note is more than just a number.

It is a reflection of how markets view growth, inflation, and risk. And lately, it’s been flashing a new message: that interest rates may remain higher for longer than many had hoped.

A Repricing of Reality

At the heart of the surge is a broad repricing of expectations. Inflation, though down from its 2022 peak, has proven stickier than the Federal Reserve anticipated.

Core prices have remained elevated, fueled by resilient consumer demand, tight labor markets, and geopolitical pressures that continue to push up commodity costs.

Recent data has only reinforced that story. March’s employment report showed stronger-than-expected job creation.

Meanwhile, factory orders and services activity point to an economy that refuses to cool on cue. Investors are now less certain that the Federal Reserve will be able—or willing—to cut rates in the near term.

For months, the bond market was betting on a pivot. Now, those bets are being unwound.

The Weight of Washington

Adding to upward pressure on yields is the ballooning supply of government debt. The Treasury Department, facing expanding deficits and rising entitlement costs, has ramped up issuance of longer-dated bonds.

The result is an imbalance: too much supply chasing cautious demand, pushing prices lower and yields higher.

Foreign appetite for U.S. debt, once a reliable source of demand, has also cooled. Rising hedging costs have made Treasurys less attractive to overseas buyers, even as the relative safety of the U.S. remains a draw.

“The fiscal side of the equation is becoming harder to ignore,” said Sarah Lansing, a fixed-income strategist at RBN Securities. “There’s a growing recognition that the market will have to absorb more debt at a time when the Fed is no longer a major buyer.”

From Wall Street to Main Street

The implications of a higher 10-year yield ripple far beyond trading floors. Mortgage rates have surged past 7.25%, putting further strain on the housing market.

The cost of financing for everything from corporate bonds to auto loans has climbed. Businesses, particularly smaller ones, are beginning to reassess investment plans.

Stocks, especially those with stretched valuations, have wobbled. The Nasdaq, after a stellar start to the year, has retreated as tech giants face renewed pressure from higher discount rates.

The S&P 500 remains volatile, caught between strong earnings on one hand and tighter financial conditions on the other.

For savers, however, the picture is brighter. After years of earning next to nothing, yields on high-yield savings accounts and certificates of deposit now offer real, inflation-adjusted returns. The 10-year yield is also restoring fixed income’s role as a genuine source of portfolio diversification.

The Fed’s Crossroads

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues find themselves navigating a narrowing path. The central bank has signaled its commitment to containing inflation, but it also recognizes the risks of over-tightening in a leveraged economy.

Officials continue to emphasize a “data-dependent” approach, leaving open the possibility of rate cuts—but not until they’re convinced inflation is durably on the decline.

Markets, for now, are less optimistic. Futures suggest that traders are pushing back expectations for any rate reduction until late 2025. With each passing month of solid economic data, that timeline extends.

“We’re in a regime where growth isn’t breaking, inflation isn’t fading fast enough, and policy has to reflect that reality,” said Leonard Kim, chief economist at Baypoint Advisors. “It’s not a crisis, but it is a reset.”

A New Normal or a Temporary Spike?

Whether this surge in yields represents a structural shift or a passing phase remains to be seen. Some analysts believe the current dynamics—a strong economy, persistent inflation, growing debt loads—could usher in a prolonged period of elevated long-term rates.

Others point to vulnerabilities beneath the surface: slowing global growth, tightening credit conditions, and the possibility that the Fed has already done enough.

In the meantime, the 10-year yield has become the market’s most important weathervane. Its movements will shape the cost of capital, the direction of equities, and the decisions made by households across the country.

For now, it’s pointing higher.

Also Read